Nanci Morris Lyon’s daughter was born the year the Pebble Mine project was first proposed in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Rylie Lyon is now a sophomore in college. She is a guide at her family’s recreational fishing operation, Bear Trail Lodge, in King Salmon, Alaska. Nanci spoke out against the mine then, and she’s still doing it today.

Talk about a telling timeline.

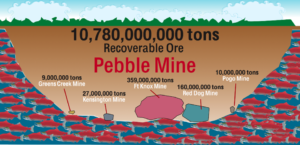

Why is it that this mining project, purported to be resting on one of the world’s largest copper, gold and molybdenum deposits, has neither begun operation nor been abandoned as a bad job in nearly 20 years? Only recently did the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers just release its Environmental Impact Statement (EIS, which would form the basis for considering possible impacts of allowing the mine to operate) for public comment.

Ponder this the next time you use your cell phone, hop online or drive to the store: Those minerals are in more everyday items than most people know. Their claimed abundance in the geologic veins hiding in the Earth’s crust near Bristol Bay has sparked much controversy during the past two decades, sometimes, pitting neighbor against neighbor in Alaska.

Why have Lyon, her family, staff, friends and most everyone else in and around the recreational, commercial and indigenous fishing industries in the Bristol Bay region continued fighting this mine for this long? That such a unified and vocal coalition of very diverse groups and cultures directly tied to the resource continues to stand united says something.

With apologies to Robert Frost, something there is that doesn’t love a mine. Particularly this mine in this spot.

Rylie Lyon with a spring rainbow trout, just a few weeks ago. Photo courtesy Nanci Lyon

In perpetuity

The biggest concern is that minerals mining produces highly toxic chemicals that permeate much of the rock and other sedimentary layers exhumed from the earth in the process to extract the desired gold, copper and molybdenum. All of that nasty stuff must be stored safely somewhere forever. Whatever happens in that watershed now has generational impacts on everything, from salmon to water to land.

Mines aren’t supposed to let that crap loose in Nature. Sadly, time and again they do. Look no further than what happened in Brumadinho, Brazil in January, or what happened at the Mt. Polley Mine in 2014.

Aftermath of Mt. Polley tailings impoundment failure. This dam was initially engineered by the same firm engineering Pebble’s dam. National Park Service Photo

People like Lyon, and my friend and colleague Melanie Brown, who fishes for sockeye salmon with her mom and other family members near Naknek, have been fighting Pebble from the beginning. Melanie’s connection to Bristol Bay traces back over generations as her family has fished those waters commercially and for subsistence with the natural rhythms of returning salmon.

Opposition to the mine stems from its proposed location just north of Lake Iliamna, in the watershed of the world’s largest wild sockeye run … and the rivers that Brown, Lyon and thousands of others depend on for their livelihoods.

They don’t view the Pebble Mine as a potential resource for their phones and computers. They view it as a ticking bomb. In their minds, the question isn’t whether something is going to go wrong. It’s when, at what scale, and whether the damage is permanent. What they fear most is the salmon won’t return.

Melanie Brown doing what she loves near Naknek. Photo courtesy Melanie Brown

Political tide change

Less than three years ago, the mine was left for dead, sentenced to purgatory by the Obama administration’s Environmental Protection Agency, which in 2014 declared the mine would violate the Clean Water Act because of its imminent threat to the wild salmon watershed. This was good news for everyone supporting the natural resource that provides a nearly $2 billion economic boost to the Alaska economy and supports over 14,000 jobs for commercial and recreational fishing businesses as well as countless related operations. Those numbers dwarf any realistic economic impact the mine would have on the state.

Then two elections happened (in 2016 and 2018), dramatically turning the political tides at both the federal and state levels and breathing life back into the project.

A 30-minute conversation between Pebble Limited Partnership CEO Tom Collier and former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt in 2017 undid all of the work that Lyon, Brown, and many, many others amassed over decades to fight the project.

I wonder if someone uttered, “Good mines make good neighbors” in that meeting.

And now the mine’s permitting process, once estimated at decades if it ever got off the ground, is on a fast track. The Corps of Engineers on Feb. 20 released its draft EIS in “record time” by many accounts. Several critics claim the EIS glazes over if not outright ignores the ample scientific, economic and straightforward concerns voiced by recreational, commercial and indigenous fishermen, business owners, residents, scientists and countless voices from outside the state.

One chief concern is that the EIS does not account for the inevitable expansion the mine would have to undergo just to try and make a profit. Read this scathing economic review by a former permitting expert with one of the world’s largest mining operations (Rio Tinto, which previously pulled away from a financial deal with Pebble Limited Partnership). According to his analysis, the mine as proposed would have a big negative net present value of -$3 billion.

And despite loud protestations to extend the comment period sufficiently to allow thorough examination of the EIS and appropriate response, the Corps seems unwilling to do so. The comment period currently ends May 30, 2019.

Passion to safeguard Nature and livelihoods. Photo: Seafood News

Worse still, the last election produced a new pro-mine governor, who has appointed pro-mine commissioners (including a former employee of Anglo American, one of the world’s largest mining operations, which also pulled away from a financial deal with Pebble) of the departments of Environmental Conservation and Fish and Game. This move essentially sets the stage to fast-track state permits (of which there are nearly 60 to secure).

Follow the money

So why the rush? If the mine is as much a fait accomplis as its backers would have you think, why are they pushing state and federal agencies, which are supposed to have the state’s best interests (read natural resources and citizens) in mind, to approve everything now?

Perhaps it’s that Pebble’s owners want the appearance of momentum to continue so they might attract yet a fifth financial backer to the altar. The previous four, including three of the four largest mining interests in the world, bailed out citing massive opposition and the risk of economic disaster.

Maybe it’s the nifty clause that promises Collier more than $12.5 million in bonus money if he secures a positive Record of Decision from the Corps of Engineers within 4 years of submission of the permit (in Dec. of 2017). That’s on top of his $2+ million salary.

Talk about scale and incentive. The tailings impoundment to hold the toxic waste produced to extract these minerals would be up to 700 feet deep and extend for several miles. And it must be secured “in perpetuity.”

This is the same Collier recently quoted railing against the mine’s opposition: “I believe that a lot of these environmental organizations choose issues in Alaska. They make them cause celebs so they can raise money around them. And they choose Alaska primarily because they don’t have to suffer the backlash from the economic impact of the project being killed because no one gives a rat’s ass what happens in Alaska.”

Is that so? Within the Bristol Bay region, opposition to the project remains at over 75 percent, with the latest state-wide poll showing 61 percent opposed across Alaska. In 2014, 65% of Alaskans voted in favor of a measure that would require approval by the state legislature (rather than simply the state Department of Environmental Services) of any mine project that would threaten salmon habitat.

Priceless habitat.

But then again, politics and money can make a difference. A ballot measure was defeated last November that would have added enforcement teeth to existing state laws that would have made permitting a mine in crucial salmon habitat harder to do. How did this happen so soon after the 2014 vote?

Because Ballot measure 1’s proponents, which included many of the same collective of fishermen, business owners and residents opposing the mine, were out-spent by several out-of-state companies. Supporters raised close to $2 million. Opponents raised close to $12 million, with the top five cash donors being such “neighbors” as Conoco Phillips ($1.4 million), BP Exploration (Remember Deepwater Horizon! $1.05 million), Donlin gold ($976,000), Hecla Mining Company, (just shy of $1 million), Coeur Alaska, (just shy of $1 million).

Oh, and let’s not forget other outside influences, such as the Koch brothers, who funded the Alaska Policy Forum, Power the Future, and Americans for Prosperity- Alaska Chapter, which operated an influence campaign to defeat Ballot Measure 1.

Profits over living natural resources, anyone?

Rolling boulders, not pebbles up hill

Certainly the mine’s operation would most significantly benefit its owners, managers and shareholders, maybe a few dozen.

On the other side of the fence are tens of thousands currently working in harmony with the salmon resource. This has been a grueling uphill battle for Lyon, Brown and everyone else standing up to outside influence. Years of persistent, grinding effort and emotion, speaking out publicly, holding signs, singing songs and writing letters take an emotional, spiritual and physical toll.

Why keep at it?

Because it’s their way of life. A connection to the land and water and salmon deeply intertwined with who they are.

Perhaps that’s a reminder of what should be important, whether we live in Bristol Bay or not. Yes, we depend on our cell phones and stuff like that. But there’s something else at work here.

Perhaps mining interests/investors/manufacturers should find the raw materials somewhere else, where there isn’t an imminent threat to a priceless resource that may not be able to recover should when something bad happens.

Can the forces working to topple a fabled stone wall in northern New England woods serve as a proxy for what’s really at risk in Bristol Bay?

Would that we could ask the salmon.

Resources

- Speak out: Your voice matters, whether you live in Alaska or not. Here’s a link to comment on the US Army Corps of Engineers draft EIS.

- Let Sen. Lisa Murkowski R-Alaska, know what you think. She needs to hear from everyone, in and out of the state. Follow the link and add additional comments if you are out of state but concerned.

- Good resource for timeline, facts and ways to engage: Save Bristol Bay

- Pebblewatch, which also has some cool maps

- National Park Service in-depth analysis of the long-term effects of tailings impoundment failures.

- A Bristol Bay fisherman speaks out in Juneau Empire op-ed against the mine.

- Op-ed by Ron Thiessen, CEO of Northern Dynasty Minerals, which owns Pebble Limited Partnership. Funny how this “neighbor” tells people not to buy into “the alarmism” about the mine, but doesn’t mention his salary is over $2 million. Even more ironic is that he encourages people to read the Army Corps of Engineers’ EIS, but fails to mention that it is incomplete and virtually ignores most of the more damning issues raised in the first phase of public comment.

- Finally, if you love wild Pacific salmon, and would like to do something beyond commenting, check out this offer from Wild for Salmon.

Top photo: Alaska Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service/Flickr

One Comment