Back in January as everyone was adjusting to a new political landscape, I was on a call with Brett Tolley of the Northwest Atlantic Marine Alliance and Bob Steneck, Professor of Oceanography, Marine Biology and Marine Policy at University of Maine. We were talking about a recent report on climate change impacts in the Gulf of Maine, and what fisheries policy may look like in the context of climate impact and the shifting political landscape.

Needless to say there were many unanswered questions. At the time, the administration threatened to cut crucial funding for Sea Grant, climate science and even some fisheries management programs. Our discussion centered on how to adapt more nimbly to climate change impacts on fisheries, and how to make fisheries management more efficient and effective. We also wondered how significantly US fisheries management could shift in a year or two.

That conversation was the seed for last Friday’s (Nov. 3) Webinar: Fisheries Management: Best Available Science May Not Be Good Enough. The discussion was a frank look at the issues with current fisheries policy based on specific examples and some speculation on what management would look like if it were more localized and relied on a different data modeling system.

Joining me on the call were David Goethel, commercial fishermen from Hampton, NH and former three-term member of the New England Fisheries Management Council; John Stoddard, New England Regional Coordinator for Health Care Without Harm’s Healthy Food in Health Care program; and Steneck.

This was a diverse panel with deep knowledge from broad perspectives. Steneck has been at the forefront of research on coral, lobsters, urchins, kelp, forage fish and species interrelationships in coastal ecosystems. Goethel has the unique experience of a commercial fishermen who has had to shift his harvest target and method because of changes in the Gulf of Maine, and who has spent several years either as an advisor to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Council or NEFMC. John Stoddard brought an institutional buyer’s perspective to the panel. He knows what healthcare representatives want from the seafood they serve their patients. They do have some concerns about sustainability, and when policy creates market forces that may limit access to locally harvested seafood, they may want to know what can be done to change the dynamic.

How’d we get here?

Steneck methodically walked us through some of the core issues with the current management system. Chief among those is the fact the Gulf of Maine, as well as other US coastal ecosystems, are changing faster than we can manage them. We have been a couple of steps behind climate change because our current data assessment system takes several years between collection and analysis and policy action. In essence, by the time policy has been set, the seascape has changed because of rising temperatures, current shifts, increased ocean acidification, etc. All of these changes have forced commercially valuable species to shift their patterns and adapt.

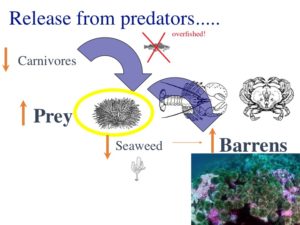

Overfishing of cod resulted in a sea urchin boom in the Gulf of Maine that collapsed in a decade. Interspecies relationships are critical to understanding dynamically changing ecosystems, and are often overlooked with current data management tools.

He pointed to the cod collapse in particular as a bellwether for how we missed the warning signs because of static data analysis, and how that type of “miss” happens frequently due to the data-intensive approach to stock assessment. He showed a brief video featuring a Canadian fisherman who said he had the trip reports to show cod stocks persistently dropping in key areas … data the government ignored because of its current management system.

Genetically distinct cod inhabit different ocean ecosystems and should be managed accordingly, not as one, all-inclusive species.

Steneck concluded that we need to “reinvent fisheries management to include multiple, independent indicators”, rather than drill down into details of one species without taking into account other critical factors such as complex interspecies relationships. Taking into account the dynamic changes within spatially appropriate areas of observation will give a more accurate view of fisheries and how quickly they change. Equally importantly, he stressed the need to expand collaboration with fishermen, mining their knowledge base to enhance data collection and analysis.

A unique point of view

David Goethel echoed those concerns. From both perspectives as fisherman and NEFMC member, he saw how current modeling methods’ stagnation meant policy did not match actual stock health and ability to withstand fishing pressure. He pointed to the impact the recent collapse of capelin in Newfoundland had on cod, seals and northern shrimp. Like Steneck, he called for managing fisheries based on the correct spatial scale and with a better understanding of changing predator-prey relationships.

Getting his point across at a management council meeting.

He also urged continued public/fishermen input at council meetings. The system breaks down when fishermen who feel disenfranchised by restrictive policies don’t participate in the process. He decried a lack of transparency in the policy process that frustrates fishermen to the point where many don’t believe it’s worth their time to speak out.

Aboard the Ellen Diane

Goethel agreed with Steneck that data poor methods based on local, spatially appropriate areas of survey would provide the local detail current “big solution” modeling misses. He also agreed that involving more fishermen in the process would play a significant role in collecting more accurate data in a timely fashion, and restoring more fishermen’s faith in the process.

A healthcare approach

Stoddard emphasized Health Care Without Harm’s mission to provide locally sourced, sustainable seafood, with a goal toward supporting community based fishermen. This is a critical issue healthcare industry staff are finding with many patients, especially in coastal New England. Some of these patients have had family or friends who fished commercially, so the some of these issues matter to them.

He said Health Care Without Harm has steadily moved away from big ecolabels such as MSC to support more locally focused programs. Stoddard highlighted a successful program by which Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary sources locally harvested seafood from Gloucester via the Gloucester Fishermen’s Wives Association. Such programs address patient demand for locally sourced seafood while strengthening healthcare institutions’ support of surrounding communities … and specifically fishermen.

Continuing the dialogue

It was a good discussion, with some engaged back and forth on next steps. For example, one of the parting questions focused on what a successful, cooperative data-poor, localized management program might look like. Steneck suggested a demonstration project within an already existing sample area (under the current management system), using a data poor assessment approach. Goethel suggested using echo system modeling that incorporates multiple species relationships, that he believes would yield a more realistic view of stock health.

The next step in the community discussion about these issues is to begin planning the next conversation. At the outset, I said we weren’t going to solve all of the issues we discussed in one conversation. But the goal is to follow up the conversation with another Webinar that explores a bit deeper what a demonstration project might look like, the type of data to study, and the hoped-for outcomes.

We will aim to set up another Webinar in the first quarter of 2018 tapping the collective knowledge of a well-informed panel, willing to explore the possibilities and elevate the discussion. Ultimately, we hope to build a foundation of knowledge that may lead to a roadmap for change.

Stay tuned.

If you’d like to view the Webinar, click on this link and then the tab that says Watch Now: Fisheries Management: Best Available Science May Not Be Good Enough.