Every time I return to New Orleans, I’m coming home to my birthplace. Profound taste memories resurface: pink roman candy stuck in my teeth, fried shrimp po’boys dripping red sauce down my arm; and the smell of a crawfish boil clinging to my hands long after I’ve sucked on the last crawdad head.

On my flight back to Maine last week, I recalled the beautiful mélange of community-building around Slow Fish values, the shared storytelling about preserving local fishing communities, and the diversity of foods and cultural narratives that made the past week so memorable.

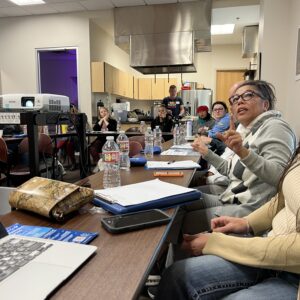

On Nov. 13, a fabulous team of chefs and fishermen¹ staged a memorable Chefs Camp at Dillard University’s Ray Charles Program in African-American Material Culture. The goal was to bring chefs representing a broad range of cultural influences into a provocative conversation about sustainable seafood sourcing.

Opportunity for dialogue

This was an extraordinary opportunity for chefs to tell fishermen what they’re looking for in terms of seafood, and for fishermen to speak truths about what happens when local chefs don’t buy local seafood in a challenging market climate.

Chefs from a broad range of cultural influences talked about some common challenges in seafood sourcing, including supply chain visibility (knowing where seafood comes from), product consistency, and fluctuating prices. Local fishermen from southern parishes shared stories about what they harvest and the staggering headwinds they face from misguided policy, markets flooded with cheap imports, climate change, and the graying of the fleet.

Graphic credit: Mara Welton, Slow Food USA Programs Director

We started the conversation by asking chefs and fishermen to provide one-word answers to what sustainable seafood means to them (see word cloud graphic above). The largest words reflect the most consensus, and therefore the focus for many of the solutions discussed below.

From there, we explored the complex global and domestic seafood supply chain and how that affects domestic seafood consumption. We discussed some of the dire ecological and socio-economic impacts of the industrialization and consolidation of the seafood industry. That includes the vast issues of corporate farmed salmon production, including disease, sea lice, feed (grinding up forage fish coastal fishing communities depend on to feed farmed salmon), and market saturation.

Local supply chain challenges

We focused on how this corporatization of the supply chain impacts local fishermen like Captain Lance Nacio and Captain Kindra Arnesen, as well as the fishing communities that Sandy Ha Nguyen of Coastal Communities Consulting represents.

All three have fiercely advocated for their fishing communities at home, in Washington, D.C., and at various fisheries council meetings and network events across the country. They are passionate about ensuring the survival of independent, community-based fishermen.

Captain Lance Nacio describing the impact of plummeting shrimp prices.

A fourth-generation shrimper, Lance, who runs Anna Marie Seafood, spoke about the changes he has seen in the 26 years since he started fishing. The recent inundation of cheap imported shrimp has pushed dock prices down below 60 cents a pound, which is a significant drop from $3.00 per pound in April of 2022. The economics are brutally unforgiving. It costs him over $8000 per trip to fuel his boat. He often has to decide whether leaving the dock is worth it. Fortunately, he has established enough personal relationships with chefs and community focused retailers that trust his product quality that he’s able to navigate the challenges. But he admits the challenges are making it harder to keep the business running.

Captain Kindra Arnesen spotlights big corporations driving industry consolidation that effectively displaces independent fishermen.

Kindra, who runs a small family fishing business with her husband David, talked about how consolidation directly affects her fishing community. She pointed to the example of one national distributor that recently purchased a local processing facility. For now, it appears the new distributor is prioritizing cheaper imported product rather than seafood harvested by local fishermen. This verticalization of the system typically forces longtime fishermen out of the industry because they often don’t have an alternative destination for processing, and therefore they have a harder time selling their harvest. She pointed to national and global organizations that claim to support sustainability but are in fact shutting out fishermen who actually care about maintaining healthy fish stocks and serving their communities.

Sandy Nguyen describes the Herculean effort to support hundreds of independent fishermen and individuals in the face of dire market conditions. Photo credit: Mara Welton

Sandy echoed this sentiment, stating quite emphatically: “What’s happening to our fishing communities is inhumane.” She spoke directly to how policies that allow for consolidation and cheap import dumping isolate fishermen to the point of surrender. Her Coastal Communities Consulting is a resource that has served over 1,500 fishermen and individuals in southern Louisiana since 2010 to provide business technical assistance, social support services, economic development, and continued disaster assistance after hurricanes and the BP oil spill. The nonprofit has seen firsthand how the current climate pushes fishermen to their limits.

Finding inspiration

Chefs asked many questions, trying to wrap their heads around the scope of the situation. Some admitted they weren’t aware of how dire the situation has become, even as they have sourced seafood from larger distributors with no supply chain visibility.

Chef Dana Honn of Carmo spoke about why he sources directly from fishermen he trusts like Lance and Kindra, and the importance of chefs eliminating waste by buying whole fish and using them nose to tail. Direct relationships eliminate the added costs and headaches of middlemen, he said. He and Chef Marcus Jacobs of Seafood Sally’s are opening Porgy’s Seafood Market to provide seafood directly from local fishermen. Dana also relayed the story of Chef Xavier Pacheco who successfully coordinated a project to develop a direct seafood system in his community in Puerto Rico by forging relationships with local fishermen and authorities. Dana pointed to this story as an example of how chefs can make a difference to community food systems.

Chef Dana Honn describes the benefits of working directly with local fishermen.

Another bright, immutable ray of hope for chefs at the camp was the passion and dedication of fishermen and advocates like Kindra, Lance, and Sandy (whose husband harvests shrimp). They love what they do. They are committed to finding ways to overcome the industrialization of the supply chain. They want to defend their fishing communities. And they want to find more ways to sell directly to more chefs who care.

So we talked about solutions.

Building community, step by step

Step one is hosting these types of conversations that allow chefs to talk about some of the issues they’ve faced in sourcing, and for fishermen to talk about the challenges they face marketing their product locally.

Step two is to brainstorm ways to create more consistent infrastructure to support direct supply chains between fishermen and chefs. One idea that percolated to the top was to develop a local processing facility that both serves and is co-managed by local fishermen. Working waterfronts that allow fishermen to offload, process, and package their product are essential to independent fishermen. This is especially important given how local processing capabilities have tailed off dramatically in recent years in coastal Louisiana due to corporate buyouts and other market factors.

Another idea centered on communication for both education (of chefs and consumers) and marketing to help spread the message: KNOW YOUR SEAFOOD! We discussed how content like the 7 C’s of Sustainable Seafood are an effective framework for discussing seafood with values. Lance cited a couple of instances when chefs and store managers didn’t know the shrimp they ordered was imported, even though it was marketed to them as coming from Louisiana. The more chefs and consumers know about the seafood they purchase, the better for local fishermen.

This was the second Chefs Camp Slow Fish North America, Slow Food USA, and One Fish Foundation have produced. The first was in Philadelphia last April in conjunction with Slow Food Philly. We will host more of these important conversations as we set out to build community between chefs and local fishermen over seafood with values.

Stellar flavors of the delicious Moqueca (Brazilian fish stew) that Dana prepared for lunch. Local shrimp, crab and fish complemented the discussion. Photo credit: Mara Welton.

Huge thanks go to Dana, (who also prepared a delectable Moqueca, a Brazilian fish stew featuring local shrimp, crabs and fish), Sandy, Kindra, and Lance for sharing their stories and bringing the conversation to area chefs. Thanks also to Zella Palmer and Jessica Bantum of Dillard University’s Ray Charles Program in African-American Material Culture for hosting the Chefs Camp.

Big shout out to chefs from GW Fins Restaurant, Fritai Nola, Maypop Restaurant, Mopho Mid-City, MISTER MAO, Seafood Sally’s, Bayona Restaurant, New Orleans, Greta’s Sushi, Addis Nola for showing up to engage in the discussion and perhaps apply some new perspective to future seafood sourcing. Additional thanks to attendees from local organizations including Where Black NOLA Eats, Black Roux Culinary Collective, MINO Foundation, and Audubon G.U.L.F.

Finally, this event would not have shone as brilliantly without the tireless efforts of Mara Welton, Slow Food USA Programs Director and my partner in months of planning for this event!

On to the next Chefs Camp. Stay tuned!

¹This is an inclusive and gender-neutral term for us, and the one used most commonly among women who fish in our networks. It’s meant to refer to those who might also use the terms fish harvesters, fisherwomen, fishermisses, fishers, and intertidal gatherers, as well as those practicing restorative aquaculture on a sustainable scale.