While planning some events for Slow Fish 2018 (April 14-16 in San Francisco), I wondered how I became steeped in Slow Fish and the idea of seafood sustainability.

I’m a journalist by trade. I started at a small town daily that required rushing to the scene of a fire, car accident or a moose running loose downtown to prove to editors we were at the scene. After 12 years of crappy pay, frayed nerves and some lifetime friendships, I jumped ship and spent a decade writing about hardware and software at a PR agency representing companies like IBM and Nokia.

I learned much in both of those jobs: How to uncover the hidden story, and how to tell it in a fashion that makes sense to a broader audience.

I backed into writing about fisheries and seafood issues after re-vamping the website of a San Diego-based sustainable fisheries apparel company in 2011. The more I learned about the complexities of fisheries policy, market dynamics, climate change and ecological impacts of different harvest and aquaculture methods, the more I wanted to know and share. A New Orleans native, I grew up with fresh local seafood all around me.

Pampano! It’s what was for dinner.

So in 2015, I started One Fish Foundation, a non-profit whose mission is to bring the sustainable seafood message into communities and classrooms from kindergarten through college.

Some people bristle at “sustainable seafood” as a meaningless cliché. I get it. “Sustainable” has been green-washed to the point of abstraction. And yet, I’ve not come across a term that is as concise and generally widely understood on first reference.

Target audience

The people I’m trying to reach when I’m talking about the perils of industrial finfish aquaculture or climate impacts on different marine species aren’t necessarily those who would react to “sustainable.”

I seek the people who go into their local grocery store and buy frozen, pre-cooked and peeled shrimp without knowing it came from Thailand. I want to talk to those who buy farmed salmon from Chile out of habit because it is cheap, and supposedly “healthy” salmon.

Lobster take-out building. Yes, they walk in and out to feed as they please. It’s just the saps who happen to be in the trap that get caught.

I remember making a poignant connection in one of my first classroom visits. It was a 6th grade geography class I’d visited two weeks before, and we’d talked about why students should care about where, how and by whom their seafood was harvested. We’d rehearsed key questions to ask when they were at a restaurant or grocery store.

At the outset of the follow-up class, one girl said she stopped her mom from ordering shrimp at a restaurant because it was from Vietnam.

I felt like I’d hit a home run.

Breaking the habit

Perhaps that’s at the heart of why I’m so deeply connected with Slow Fish. Most people nod their heads when they learn that 90% of the seafood we eat in this country is imported. But they shudder to learn that a staggering amount of that seafood is coming from countries that pound their products with hormones to make them grow fast or antibiotics to fight disease.

We won’t change that import dynamic without many frank conversations. The Slow Fish mission to ensure everyone has access to good, clean and fair seafood is at the core of these conversations. When I’m talking to a large group of people, I ask them why they think that 90% figure persists. They mention price, policy and complex market dynamics. All of these are key drivers.

Anyone who loves seafood and cares about the resource and the fishermen who harvest it sustainably can be part of the Slow Fish movement. Photo: Kate Masury at Slow Food Nations, Denver, July 2017

But I think another critical factor is habit. Consumer habit drives the equation because people buy what is cheap without checking the provenance of the food they eat. Policy habit also plays a role. There seems to be no urgency to fix policy that allows cheap foreign imports to flood U.S. markets, while a big chunk of domestically harvested seafood goes offshore for astronomical prices.

And the disconnect continues.

The Slow Fish San Francisco mission

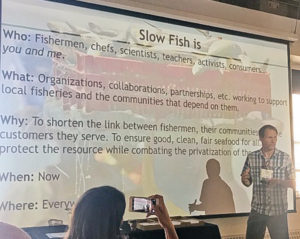

Slow Fish aims to change that. While combating inequities in the system that often favor concentrating power and influence in the hands of a few big fishing operations, we also highlight the successes of small-scale operations to bring local, responsibly harvested seafood to their communities and beyond. We encourage people and groups to collaborate on complex issues.

Witness the fierce opposition to the proposed Pebble Mine at the headwaters of the world’s most significant wild salmon run in Bristol Bay, Alaska. But for the persistent collaboration between commercial, recreational and indigenous fishermen, along with advocates and regional politicians, that copper mine would already be up and running. (Check out the We Are Bristol Bay fundraiser dinner at Slow Fish San Francisco on April 15 to eat delicious wild sockeye salmon and talk to the fishermen who may have caught it and learn about why opposing the mine matters.)

Dinner and conversation give attendees the chance to engage in the seafood issues that matter. A similar scene will take place on April 15 in San Francisco at the We are Bristol Bay Dinner.

This is just one of the topics we’ll cover at Slow Fish San Francisco April 14-16. We’ll talk about the graying of the fleet and innovative ways to attract and support more young fishermen into the profession. We’ll talk about women in fisheries, how to support artisanal fisheries and explore a new mission to reduce domestic seafood imports from 90% to 50% by 2050.

And we’ll have an interactive group discussion on Slow Fish 101, discussing what Slow Fish is and does, what its values are, and how we can grow the network. As the Slow Fish network expands, we fuel collaboration and innovation to solve some of the challenges we face in ensuring good, clean and fair seafood for all.

Come join us! Learn about why you should care, and what you can do to help affect positive change. Here is a link to the Slow Fish website where you’ll find tickets, a schedule and more information about why you’ll want to attend.