Attending Slow Food Nations in Denver this past weekend, I had some expectations about the Slow Fish 101 presentation I would co-lead and the gumbo I would make.

As often happens, those expectations capsized last minute and I and many others had to adapt on the fly. For the second year in a row, the Slow Fish USA team had to respond quickly to a variety of circumstances outside our control.

In the midst of towed vehicles, last-minute technical presentation difficulties, and a bit of a cluster around the commissary kitchen, we scrambled to help each other out. And just as we did last year at the Slow Fish gathering in New Orleans, we made it work… well.

Blame it on the weather

Again, weather played a role, as it did last year when we had to change venues because a flood warning closed down the original host site. This time, I learned my Slow Fish 101 co-presenter Paul Molyneaux was stranded in Portland, Maine because of weather and would miss the presentation. Having fished commercially and written several books and articles about fisheries, Paul not only brings 40 years of experience to the conversation, he has also made important connections all over the world.

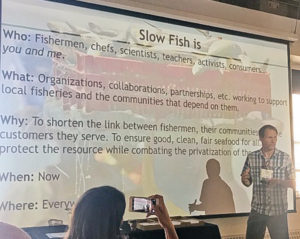

Anyone who loves seafood, cares about the resource and the fishermen who harvest it sustainably can be part of the Slow Fish movement. Photo: Kate Masury

We each had developed a portion of the deck, and his relied heavily on his global travels learning from and supporting artisanal fishermen and their efforts to thrive. I learned much about these issues from our discussions, but I didn’t feel good about trying to put my perspective on the narrative of all of his slides. So I was up until 11:30 the night before tweaking the slide deck to convey many of the same messages, but from a perspective I’m more comfortable with.

Slow Fish USA luminary Kevin Scribner prefaced the presentation next morning with a history of Slow Fish and provided valuable context for questions and discussion flow.

And it was a good discussion. The audience was a mix of Slow Fish representatives and Slow Food delegates interested in fisheries issues. We reviewed some compelling statistics demonstrating how current industrial seafood markets are stacked against small- and mid-scale fishermen.

We also discussed how Slow Fish empowers these fishermen around the world to compete in local and global markets using examples such as the Tuna Harbor Dockside Market in San Diego, Know Fish Dinners in New Hampshire and Maine, and projects that support artisanal fishermen in Uganda and Thorupstrand, Denmark.

Tuna Harbor Dockside Market, San Diego. Photo: courtesy THDM.

Tuna Harbor Dockside Market is a shining example of multi-tiered collaboration between fishermen, activists and government. More than three years ago, a group of San Diego fishermen sought a way to sell to consumers direct off the boat. Though there was no specific permit that would allow that type of retail setup, the city, county and state worked together to create legislation that supports the market.

The result?

- Fishermen have created relationships with customers.

- They’ve earned more money: sea urchin prices jumped from $.80 to $5 per lb. and mackerel rose from $.30 to processors to $4 per lb. to consumers.

- Fishermen have changed the way they fish to accommodate market demand.

- Fishermen’s families work the tents, getting their children’s hands on the product.

The audience posed great questions about aquaculture, fisheries management and the long-term prospects of wild harvest in the face of growing demand. The conversations continued even after we were kicked out of the room as the next group set up.

First mission accomplished.

Blood, sweat and gumbo

The plan was to highlight the story behind the fabulous shrimp and crabs from Lance Nacio’s Anna Marie Shrimp in Louisiana via gumbo. I also secured some of the best andouille sausage I’ve ever had from Toby Rodriguez, a born-on-the-bayou, pig whisperer, traditional butcher and co-owner of Lache Pas Boucherie and Cuisine in Lafayette, La. He had me at “I call bullshit on all commercially available andouille!”

The BIG challenge was logistics, such as sourcing a 40-quart stockpot, stirrer, ladle and all of the flour, vegetables, oil etc. I’d need to deliver my standard of gumbo. I also needed a place to prep and make a stock. Even with weeks of planning, this still proved to be much more challenging than we expected or was necessary.

Thanks guidance from some chef friends, this was NOT a disaster.

Fortunately, because of the connections I’ve forged with Slow Fish and some outstanding chefs, I found what I needed. A couple of chefs, Kelly Whitaker of Basta in Boulder, and my dear friend Evan Mallett of Black Trumpet in Portsmouth, NH helped me figure out how to cook up about 30 pounds of rice (which was way out of my comfort zone.) Evan also chopped and connected me with a chef for the pot and three locally sourced chickens.

I prepped with help from old and new friends for nearly seven hours after presenting. The morning of the food service, I got a late start because we had to wait for the health inspector and I had to try and figure out how to get 50+ pounds of food in different containers and 12 quarts of stock from the commissary kitchen 5 blocks to the site where I’d cook the gumbo. With a dolly and someone’s truck, we made it work.

Lance’s blue claw crabs added flavor…and some down-and-dirty eating for lucky patrons.

Four hours, a few laughs, a couple of cuss words, a stream of sweat and an unfortunate slip of a knife later, and I was ladling gumbo to praise. We had three tents serving fried shrimp, Baja oysters, miso and seaweed, Alaska salmon, salmon poke and black cod. All of it delicious. The quality and freshness of each product was exceptional.

The moment of truth for me came late that afternoon when an elderly African American man sporting a comfortable sun hat and shades asked, “What you got in that gumbo, son?”

I told him the ingredients, mentioning Toby’s sausage, and the fact I smoked the chicken over apple wood that morning.

“Where you from?”

“New Orleans, sir.”

“Who taught you?”

“A Creole woman who took care of me when both my parents were working. Nothing written down. All oral tradition. Took two years of her whacking me over the head with a wooden spoon every time I messed up for me to start getting it right.”

“Ok. Let’s try it,” he said, dropping his ticket in the cup.

Nervously, I spooned out some rice and carefully selected a ladle that had shrimp, crab, two different kinds of sausage, chicken and as many vegetables as could fit.

The man took a spoonful and seemed to swirl the gumbo around in his mouth like a sommelier, which made me uncomfortable. If he didn’t like it, my day was lost.

He raised his head, sniffed, then a slight smile curled his mouth.

“A lot of flavors that work well together.”

“You like it?” I asked, for confirmation.

“Yes. You done good. Thank you.”

“Thank you, sir!!!”

Notice the gloved hand.

So what if I may have shaved some time off the back end of my life stressing over logistics. So what if I’m now struggling to type with nine fingers because I damn near sliced off the tip of my index finger early in the morning before really getting going on the gumbo. Someone in the tent trained in wilderness survival did a field repair to stop the bleeding so I could complete the mission. I got four stitches only after most of the gumbo was gone and I received “official” validation.

Group effort

All of this goes back to something Slow Food USA director (and former New Orleans high school classmate) Richard McCarthy said in opening remarks that Slow Food is about pluralism. Change doesn’t come from any one person. It comes from a collective force.

So it is true with Slow Fish and specifically, my mission with One Fish Foundation. Changing attitudes about consumer food and seafood purchases requires a group effort. It requires communication, collaboration, partnerships and adaptation. Adapting to unforeseen challenges to event execution is becoming an illustrative trend for Slow Fish USA. It’s because of the connections and friendships we’ve formed that we’ve been able to overcome some last-minute hurdles, working together to send our message.

It’s because of those connections, and the new connections we make that we will continue to steer the conversation toward preserving the seafood resource and the way of life of the fishermen who harvest and care for it.

Top Photo: Don’t forget the secret ingredient! Credit: Lance Nacio.

One Comment