Last week, One Fish Foundation visited Portland High School for the third year in a row to discuss seafood sustainability with seniors taking a Marine Sciences course. Intern Jennifer Halstead, a senior at the University of New Hampshire, adeptly presented a clear, concise and digestible explanation of ocean acidification and how it is affecting cornerstone Gulf of Maine species like lobster and mussels. In this guest blog, Jennifer discusses the importance of taking advantage of opportunities to speak to students and community members about ocean acidification, other challenges our oceans face with climate change, and why we all need to be involved.

By Jennifer Halstead

Speaking to a crowd of people, no matter the size or demographic, can be at once daunting and rewarding, especially for a college student. Truly. It’s empowering to have people listen to your words. It’s uplifting to have them ask questions and even challenge your ideas.

Talking to a small class of students at Portland High School last week was no different. Ocean acidification (OA) is something that’s not easy to wrap your head around, but these students understood the urgency related to the issue. If at least one of them continues to ask questions and be curious, I feel as though I did my job.

Sadly, we don’t know how acidification is going to impact lobsters, one of the most important economic industries in Maine (the entire industry, including the supply chain is valued at over $1 billion). [Lobster harvests already face threats from the rapidly warming Gulf of Maine. A recent study suggests the lobster harvest could decline by as much as 62% by 2050 if the Gulf of Maine keeps warming at its current pace].

As concerned citizens and scientists, we need to start asking more questions and demanding more answers. And that is how we create change. The power is in your hands – our hands – to save oceans and our beloved lobster rolls.

I’ve spent a good portion of my college career learning about OA. Unfortunately, while our understanding of the impacts of OA is growing, OA is occurring more rapidly than we can keep up with in some places, including the Gulf of Maine. The West Coast has dealt with OA fallout, such as steep declines in oyster hatchery production in 2005, which threatened economics and 130 years of oyster hatchery history. In the Gulf of Maine, we haven’t seen complete devastation yet, but top scientists fear that it’s coming, and so do I.

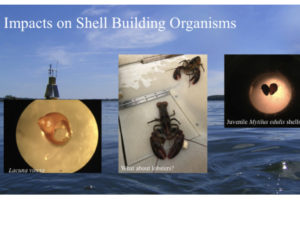

Part of Jennifer’s research on OA: a type of sea snail on the left, and blue mussel on the right. Both the sea snail and the half mussel shell you can almost see through (on the right) were exposed to acidic water. Increased acidity in the ocean weakens many shellfish’s capabilities to calcify their shells and protect themselves from disease. Credit: Jennifer Halstead.

We understand climate change impacts like OA, temperature, salinity, and currents, but not the details of how they interact and impact different species. We don’t understand the entire system. We only understand the pieces. Imagine trying to put a puzzle together with no idea what the end result is supposed to look like. That’s the immense challenge of trying to understand climate change impacts here in the Gulf of Maine and elsewhere; things are happening now that we won’t fully realize for several months, or even years.

To move forward and get research to catch up with the changes in the Gulf of Maine, we need the public’s interest and support. We need people to ask questions and demand answers. Spreading the word about these issues through presentations and hands-on demonstrations is a key piece to garnering support for these causes. Every time I stand in front of a group of people and talk to them about acidification, I can see us moving forward. Future generations are interested in problems, but even more interested in pushing for solutions.

As a college student, I often get asked where I see myself in 5 years, or what I want to do after I graduate. My broad answer is that I hope to be doing something to change the world for the better. To do that, I’ll keep standing in front of crowds of people, telling them about problems our oceans face, and asking for their help in saving them.