I often talk about “democratizing the message.” That is, I want to reach the largest audience across the broadest demographic possible: different age groups, cultural backgrounds, economic brackets, life experiences…everything. In short, the entire social fabric that relies on seafood for part of its diet.

Why? Because fundamental societal change doesn’t happen within only one demographic. This type of change may start in one group, but must transcend differences to scale up to have societal impact. This is especially true for the domestic seafood supply chain. Habit and price, fueled by an industrialized global seafood supply chain, are the main drivers behind the fact that 90% of the seafood we eat in the US is imported. That’s why we need to speak to the broadest range of seafood consumers.

The goal in these conversations is to provide new perspective that might help consumers, regardless of demographic, make better choices for themselves, the resource and fish harvesters in and around their communities. There are health and socio-economic costs of that frozen shrimp from Thailand that offset the cheaper price. If people I’ve spoken to choose the cheaper imported product for whatever reason (often price is the limiting factor, which is a much larger food and social justice issue), they do it with a broader understanding of the consequences of that decision. Hopefully we can work toward re-localizing our seafood supply chain so folks of all incomes can find local, responsibly harvested, affordably priced species, especially under-utilized species like dogfish or scup.

And it all starts with education.

So, where can I find an audience with a range of cultural backgrounds, socioeconomic circumstances and life experiences? Our public schools bring together a cross section of society each day. I jumped at the opportunity to join students and teachers at two of Portland’s three public middle schools this spring.

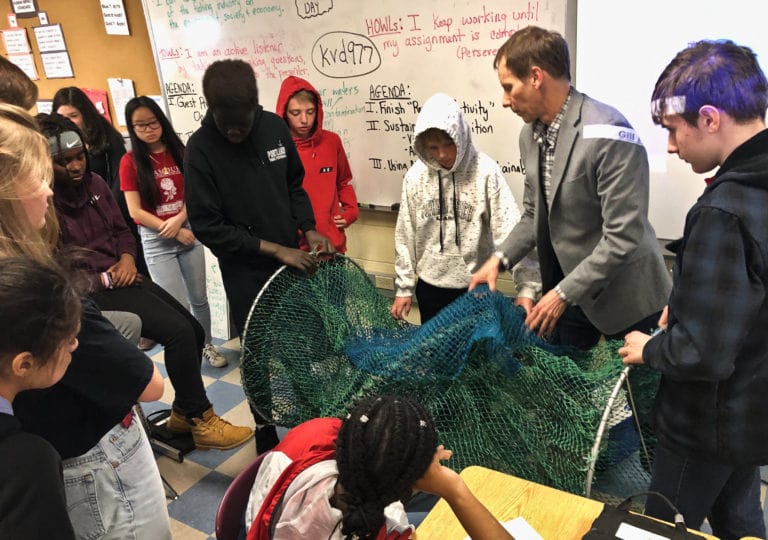

The Turtle excluder device is cumbersome, but a great hands-on tool for explaining innovation to reduce bycatch. photo: Lincoln Middle School Teacher Christel Driscoll

I seized the opportunity to democratize the message among students coming from diverse cultural backgrounds with respect to seafood while visiting classes at Lyman Moore Middle School and Lincoln Middle School a few weeks ago.

At Lyman Moore, I spoke to four large groups of 7th graders who reveled in laying hands on gill net, a turtle excluder device and a 24 oz. metal jig with some serious hooks. Fortunately, no one had to visit the school nurse afterward.

They also had the option to touch a dead black sea bass as we learned about why this mid-Atlantic species is showing up in lobster traps in and around Casco Bay, and the implications for marine ecosystem balance. This became a discussion about species adaptation as the Gulf of Maine continues to warm, and how climate change could impact what seafood is available down the road. We also talked about black sea bass as a local, underutilized species.

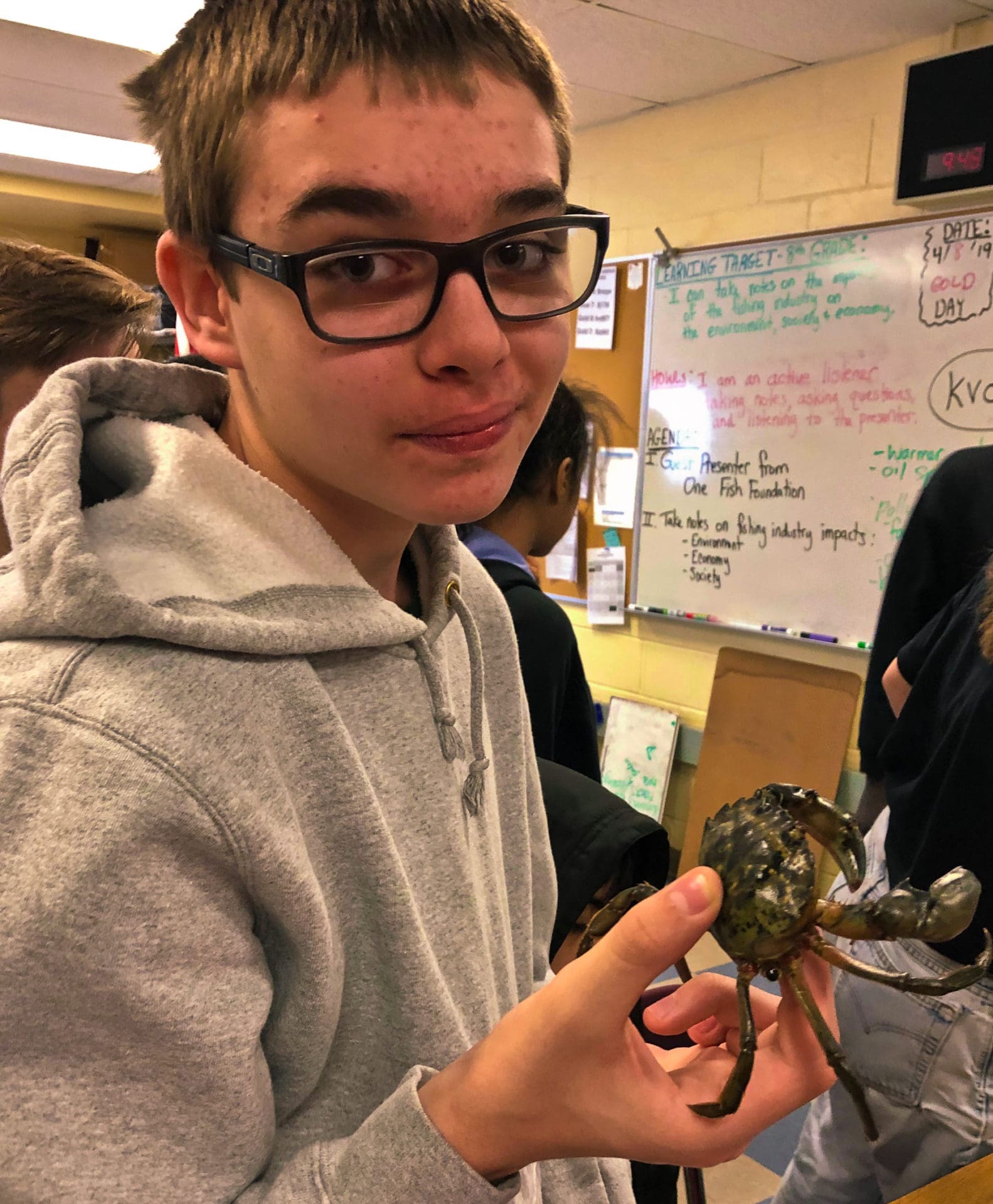

Live European green crabs held center stage as the keystone climate change adaptor species during the visit to Lincoln Middle school where I spoke with two classes of 8th graders taking a Sustainability Science course. The classroom, featuring a stove, sink, refrigerator and some counter space harkened back to the seemingly long-ago days of Home Economics.

“Can I keep it as a pet?” is one of the most common questions I get. Occasionally, when I ask what they’d do with it, I get, “I’ll feed it to my dog.” Ok. Eat the invasives!

This proved to be a perfect backdrop for discussing efforts to turn humans into pest control when it comes to green crabs, which are very fertile, very destructive (eating our mussels, clams and oysters at alarming rates) and have no significant natural predators. We also talked about industrial aquaculture, and how domestically grown oysters, mussels, clams and seaweed solve many of the serious issues with large-scale finfish aquaculture such as salmon (disease, sea lice, antibiotic use, feed sourcing and health and environmental impact).

In both schools, students took notes, asked questions and in some cases, showed a genuine interest in this new perspective: their decisions, whether they eat seafood or not, matter. Choosing locally harvested mackerel matters. Foregoing the single-use straw matters.

I passed out the 7 C’s of Sustainable Seafood in hopes they would take it home, put it on the fridge and have a conversation with their families and friends.

This is one important way to spread the message … regardless of demographic.

How do I know I made an impact? Among the several thank-you notes I received was one from a student whose uncle is from Senegal. I had spoken about how industrial Chinese fleets are vacuuming up the sardinella, anchovetta and mackerel artisanal and subsistence fishermen in West Africa depend on for their lives.

“All of these issues impact my future and hearing about the lack of knowledge many people have is very concerning, but I’m sure that eventually people will come to their senses and do something,” wrote the student.

Yes, people will come to their senses, hopefully, if we keep having conversations like this with people from diverse backgrounds.