With apologies to Charles Dickens, the Tale of Two Salmon began with a description of how it was the best of times, and then, how it was the worst of times.

How one species, Atlantic salmon, was pushed to near extinction because of 300+ years of intense fishing and damming of much of its critical habitat throughout New England and into Canada. How another group of salmonids, wild Pacific salmon (including king, sockeye, coho, pink and chum) were given lifelines by better management and some degree of habitat preservation.

And how the Pacific salmon in Alaska continue to provide largely abundant runs, serving a variety of stakeholders including commercial, recreational and subsistence fish harvesters. We discussed how policy there is a dynamic tool that better incorporates input from these different stakeholders, as well as up-to-the-minute harvest and escapement (fish that continue upstream to spawn) analysis to determine how and when the harvest starts and stops.

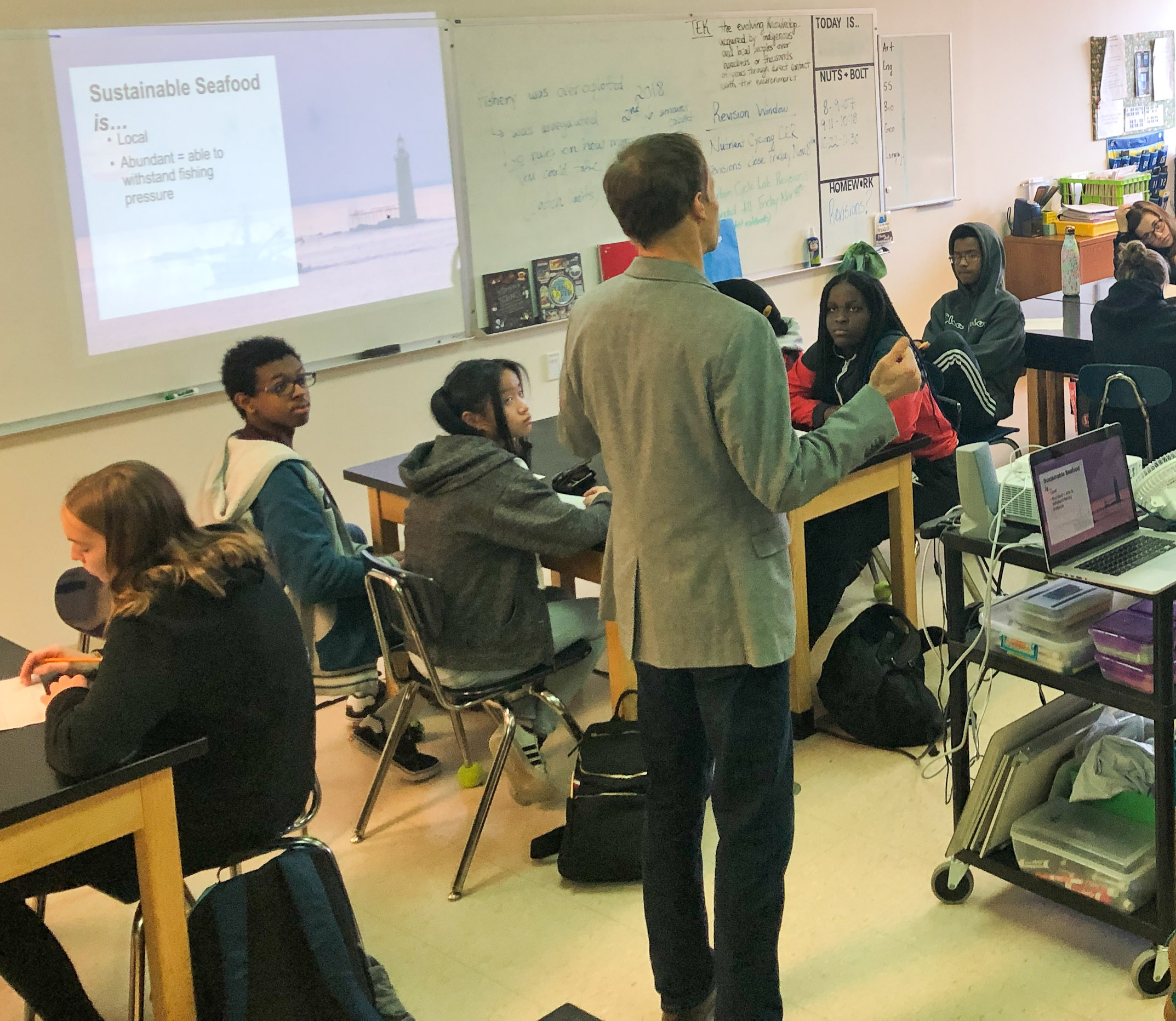

The focus on indigenous subsistence fishing was of particular importance to the 9th graders in Jenny Crowley’s ecology class at Casco Bay High School for Expeditionary Learning in Portland last month. They were learning about human interaction with natural resources and the impact humans can have on their surrounding environments. CBHS immerses students in “expeditions,” which allow them to dive deep into particular issues or topics while incorporating other facets of their education.

We talked about the delicate balance of policy on how to ensure different stakeholders have fair access to the resource. I shared my experience in Bristol Bay, Alaska this summer, talking with indigenous and subsistence fish harvesters there who described the traditions of learning to live in harmony with the salmon, the water and the land.

Finding that natural balance, taking only what they need to eat throughout the year and passing on that knowledge (like how to properly fillet a salmon using a traditional ulu knife and how to use the entire fish) are essential to maintaining that harmony from generation to generation.

Pebble Mine exploration site. I took this photo during a flight to see how the mine would affect the headwaters of the world’s largest wild salmon run. I shared other photos depicting the breathtaking landscape that is veined with water. Students understood this one human “input” could result in devastation of that habitat.

We also spoke about how the different user groups in Alaska have united together in the past nearly two decades in solidarity to oppose the proposed Pebble Mine. It is largely due to that collaboration and the fierce determination to protect the resource that the proposed gigantic open pit copper and gold mine has not yet been built.

We talked about the tragedy of the commons and how communities working together to determine how best to manage the resource so it continues to provide for the entire community is absolutely essential.

So the students and I took those expeditions together in one-hour increments, talking about important socio-economic issues and how our choices affect the salmon and all marine life.

Collectively, we came to the conclusion that the type of community thinking in Alaska is one reason wild Pacific salmon there shade closer to the best of times.

Perhaps we should apply that model more diligently elsewhere.